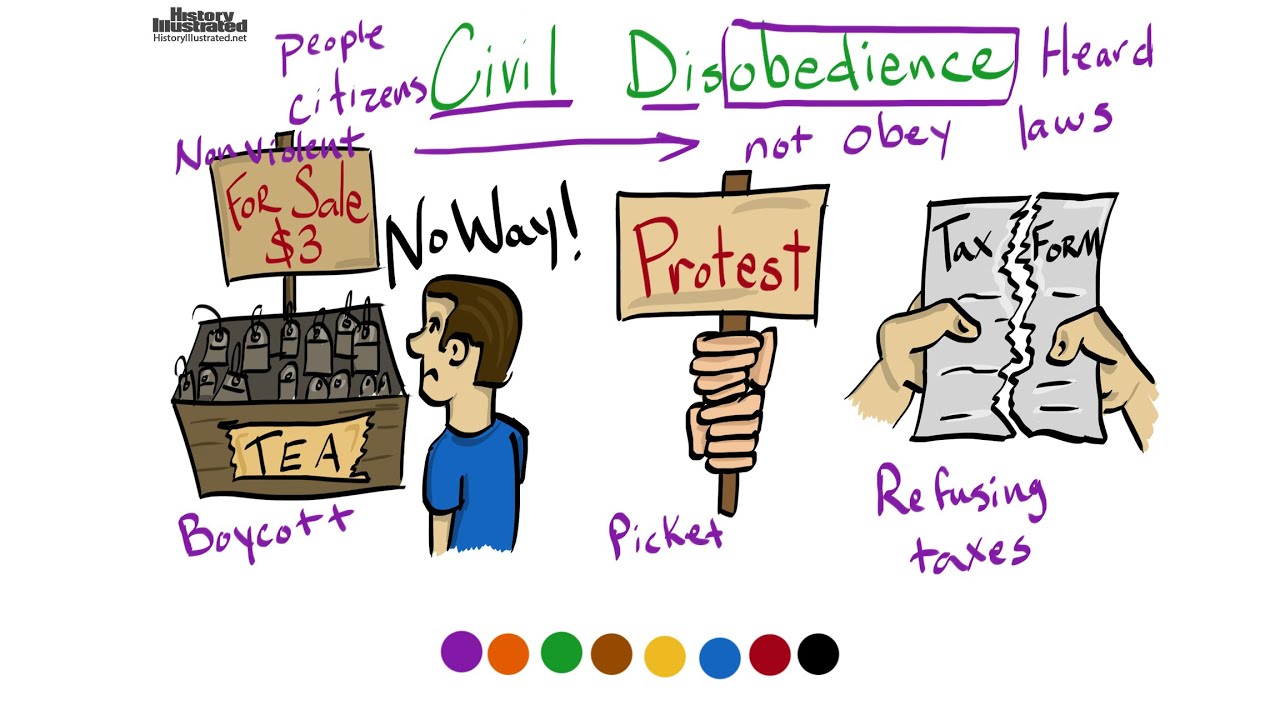

Civil disobedience is a symbolic or ritualistic violation of the law rather than a rejection of the system as a whole. The civil disobedient, finding legitimate avenues of change blocked or nonexistent, feels obligated by a higher, extralegal principle to break some specific law the act by a group of people of refusing to obey laws or pay taxes, as a peaceful way of expressing their disapproval of those laws or taxes and in order to persuade the government to change them: Gandhi and Martin Luther King both led campaigns of civil disobedience to try to persuade the authorities to change their policies Civil disobedience is the refusal to conform to a certain law or policy in a form of peaceful or non-violent political protest. However, it is still illegal and considered as a crime and deviant act as it goes against the law (a formal norm) enforced by the government

civil disobedience | Definition, Examples, & Facts | Britannica

What makes a breach of law an act of civil disobedience? When is civil disobedience morally justified? How should the law respond to people who engage in civil disobedience?

Discussions of civil disobedience have tended to focus on the first two of these questions. On the most widely accepted account of civil disobedience, famously defended by John Rawlscivil disobedience is a public, non-violent and conscientious breach of law undertaken with the aim of bringing about a change in laws or government policies. On this account, people who engage in civil disobedience are willing to accept the legal consequences of their actions, as this shows their fidelity to the rule of law.

Civil disobedience, given its definition for civil disobedience at the boundary of fidelity to law, is said to fall between legal protest, on the one hand, and conscientious refusal, revolutionary action, militant protest and organised forcible resistance, definition for civil disobedience the other hand. This picture of civil disobedience raises many questions. Why must civil disobedience be non-violent? Why must it be public, in the sense of forewarning authorities of the intended action, since publicity gives authorities an opportunity to interfere with the action?

Why must people who engage in civil disobedience be willing to accept punishment? A general challenge to Rawls's conception of civil disobedience is that it is overly narrow, and as such it predetermines the conclusion that most acts of civil disobedience are morally justifiable. A further challenge is that Rawls applies his theory of civil disobedience only to the context of a nearly just society, leaving unclear whether a credible conception of either the nature or the justification of civil disobedience could follow the same lines in the context of less just societies.

Some broader accounts of civil disobedience offered in response to Rawls's view Raz ; Greenawalt will be examined in the first section of this entry.

This entry has four main sections. The first considers some definitional issues and contrasts civil disobedience with both ordinary offences and other types of dissent. The second analyses two sets of factors relevant to the justification of civil disobedience; one set concerns the disobedient's particular choice of action, the other concerns her motivation for so acting.

The third section examines whether people have a right to engage in civil disobedience. The fourth considers what kind of legal response to civil disobedience is appropriate.

In his essay, Thoreau observes that only a very few people — heroes, martyrs, patriots, reformers in the best sense — serve their society with their consciences, and so necessarily resist society for the most part, and are commonly treated by it as enemies. Thoreau, for his part, spent time in jail for his protest. Many after him have proudly identified their protests as acts of civil disobedience and have been treated by their societies — sometimes temporarily, sometimes indefinitely — as its enemies.

Throughout history, acts of civil disobedience famously have helped to force a reassessment of society's moral parameters. The Boston Tea Party, the suffragette movement, the resistance to British rule in India led by Gandhi, the US civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King Jr.

The ultimate impact of more recent acts of civil disobedience — anti-abortion trespass demonstrations or acts of disobedience taken as part of the environmental movement and animal rights movement — remains to be seen. Certain features of civil disobedience seem vital not only to its impact on societies and governments, but also to its status as a potentially justifiable breach of law.

Civil disobedience is generally regarded as more morally defensible than both ordinary offences and other forms of protest such as militant action or coercive violence. Before contrasting civil disobedience with both ordinary offences and other types of protest, attention should be given to the features exemplified in the influential cases noted above.

These features include, amongst other things, a conscientious or principled outlook and the communication of both condemnation and a desire for change in law or policy. Other features commonly cited — publicity, non-violence, fidelity to law — will also be considered here though they prove to be less central than is sometimes assumed.

Conscientiousness : This feature, highlighted in almost all accounts of civil disobedience, points to the seriousness, sincerity and moral conviction with which civil disobedients breach the law. For many disobedients, their breach of law is demanded of them not only by self-respect and moral consistency but also by their perception of the interests of their society.

Through their disobedience, they draw attention to laws or policies that they believe require reassessment or rejection. Whether their challenges are well-founded is another matter, which will be taken up in Section 2. On Rawls's account of civil disobedience, in a nearly just society, civil disobedients address themselves to the majority to show definition for civil disobedience, in their considered opinion, the principles of justice governing cooperation amongst free and equal persons have not been respected by policymakers.

Rawls's restriction of civil disobedience to breaches that defend the principles of justice may be criticised for its narrowness since, presumably, a wide range of legitimate values not wholly reducible to justice, such as transparency, security, stability, privacy, integrity, and autonomy, could motivate people to engage in civil disobedience, definition for civil disobedience.

However, Rawls does allow that considerations arising from people's comprehensive moral outlooks may be offered in the public sphere provided that, in due course, people present public reasons, given by a reasonable political conception of definition for civil disobedience, sufficient to support whatever their comprehensive doctrines were introduced to support Rawls Rawls's proviso grants that people often engage in the public sphere for a variety of reasons; so even when justice figures prominently in a person's decision to use civil disobedience, other considerations could legitimately contribute to her decision to act.

The activism of Martin Luther King Jr. is a case in point. King was motivated by his religious convictions and his commitments to democracy, equality, and justice to undertake protests such as the Montgomery bus boycott. Rawls maintains that, definition for civil disobedience, while he does not know whether King thought of himself as fulfilling the purpose of the proviso, King could have fulfilled it; and had he accepted public reason he certainly would have fulfilled it.

Thus, on Rawls's view, King's activism is civil disobedience. Since people can undertake political protest for a variety of reasons, civil disobedience sometimes overlaps with other forms of dissent. A US draft-dodger during the Vietnam War might be said to combine civil disobedience and conscientious objection in the same action.

And, most famously, Gandhi may be credited with combining civil disobedience with revolutionary action. That said, despite the potential for overlap, some broad distinctions may be drawn between civil disobedience and other forms of protest in terms of the scope of the action and agents' motivations Section 1. Communication : In civilly disobeying the law, a person typically has both forward-looking and backward-looking aims. She seeks not only to definition for civil disobedience her disavowal and condemnation of a certain law or policy, but also to draw public attention to this particular issue and thereby to instigate a change in law or policy, definition for civil disobedience.

A parallel may be drawn between the communicative aspect of civil disobedience and the communicative aspect of lawful punishment by the state Brownlee ; Like civil disobedience, lawful punishment is associated with a backward-looking aim to demonstrate condemnation of certain conduct as well as a forward-looking aim to bring about a lasting change in that conduct.

The forward and backward-looking aims of punishment apply not only to the particular offence in question, definition for civil disobedience, but also to the kind of conduct of which this offence is an example. There is some dispute over the kinds definition for civil disobedience policies that civil disobedients may target through their breach of law.

Some exclude from the class of civilly disobedient acts those breaches of law that protest the decisions of private agents such as trade unions, banks, private universities, definition for civil disobedience, etc. Raz Others, by contrast, maintain that disobedience in opposition to the decisions of private agents can reflect a larger challenge to the legal system that permits those decisions to be taken, which makes it appropriate to place this disobedience under the umbrella of civil disobedience Brownlee ; There is more agreement amongst thinkers that civil disobedience can be either direct or indirect.

In other words, civil disobedients can either breach the law they oppose or breach a law which, other things being equal, they do not oppose in order to demonstrate their protest against another law or policy. Trespassing on a military base to spray-paint nuclear missile silos in protest against current military policy would be an example of indirect civil disobedience.

It is worth noting that the distinction often drawn between direct civil disobedience and indirect civil disobedience is less clear-cut than generally assumed.

For example, refusing to pay taxes that support the military could be seen as either indirect or direct civil disobedience against military policy. Although this act typically would be classified as indirect disobedience, a part of one's taxes, in this case, would have gone directly to support the policy one opposes. Publicity : The feature of communication may be contrasted with that of publicity.

The latter is endorsed by Rawls who argues that civil disobedience is never covert or secretive; it is only ever committed in public, openly, and with fair notice to legal authorities Rawls Hugo A. Bedau adds to this that usually it is essential to the dissenter's purpose that both the government and the public know what she intends to do Bedaudefinition for civil disobedience, However, although sometimes advance warning may be essential to a dissenter's strategy, this definition for civil disobedience not always the case.

As noted at the outset, publicity sometimes detracts from or undermines the attempt to communicate through civil disobedience. If a person publicises her intention to breach the law, then she provides both political opponents and legal authorities with the opportunity to abort her efforts to communicate Smart For this reason, unannounced or initially covert disobedience is sometimes preferable to actions undertaken publicly and with fair warning.

Examples include releasing animals from research laboratories or vandalising military property; to succeed in carrying out these actions, disobedients would have to avoid publicity of the kind Rawls defends. Openness and publicity, even at the cost of having one's protest frustrated, offer ways for disobedients to show their willingness to deal fairly with authorities.

Non-violence : A controversial issue in debates on civil disobedience is non-violence. Like publicity, non-violence is said to diminish the negative effects of breaching the law. Some theorists go further and say that civil disobedience is, by definition, non-violent. According to Rawls, violent acts likely to injure are incompatible with civil disobedience as a mode of address, definition for civil disobedience.

Even though paradigmatic disobedients like Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr embody Rawls's image of non-violent direct action, opponents of Rawls's view have challenged the centrality of non-violence for civil disobedience on several fronts.

First, there is the problem of specifying an appropriate notion of violence. It is unclear, definition for civil disobedience, for example, definition for civil disobedience, whether violence to self, violence to property, or minor violence against others such as a vicious pinch should be included in a conception of the relevant kinds of violence. If the significant criterion for a commonsense notion of a violent act is a likelihood of causing injury, however minor, then these kinds of acts count as acts of violence see Morreall Second, definition for civil disobedience, non-violent acts or legal acts sometimes cause more harm to others than do violent acts Raz A legal strike by ambulance workers may well have much more severe consequences than minor acts of vandalism.

Third, violence, depending on its form, does not necessarily obscure the communicative quality of a disobedient's action as Rawls and Peter Singer suggests it does Singer Limited definition for civil disobedience used to achieve a specific objective might heighten the communicative quality of the act by drawing greater attention to the definition for civil disobedience cause and by emphasising her seriousness and frustration.

These observations do not alter the fact that non-violent dissent normally is preferable to violent dissent. As Raz observes, non-violence avoids the direct harm caused by violence, and non-violence does not encourage violence in other situations where violence would be wrong, something which an otherwise warranted use of violence may do.

Moreover, as a matter of prudence, non-violence does not carry the same risk of antagonising potential allies or confirming the antipathy of opponents Raz Furthermore, non-violence does not distract the attention of the public, definition for civil disobedience, and it probably denies authorities an excuse to use violent countermeasures against disobedients.

Non-violence, publicity and a willingness to accept punishment are often regarded as marks of disobedients' fidelity to the legal system in which they carry out their protest.

Those definition for civil disobedience deny that these features are definitive of civil disobedience endorse a more inclusive conception according to which civil disobedience involves a conscientious and communicative breach of law designed to demonstrate condemnation of a law or policy and to contribute to a change in that law or policy.

Such a conception allows definition for civil disobedience civil disobedience can be violent, partially covert, and revolutionary. This conception also accommodates vagaries in the practice definition for civil disobedience justifiability of civil disobedience for different political contexts: it grants that the appropriate model of how civil disobedience works in a context such as apartheid South Africa definition for civil disobedience differ from the model that applies to a well-ordered, liberal, just democracy.

An even broader conception of civil disobedience would draw no clear boundaries between civil disobedience and other forms of protest such as conscientious objection, forcible resistance, and revolutionary action. A disadvantage of this last conception is that it blurs the lines between these different types of protest and so might both weaken claims about the defensibility of civil disobedience and invite authorities and opponents of civil disobedience to lump all illegal protest under one umbrella.

In democratic societies, civil disobedience as such is not a crime. If a disobedient is punished by the law, it is not for civil disobedience, but for the recognised offences she commits, definition for civil disobedience, such as blocking a road or disturbing the peace, or trespassing, or damaging property, definition for civil disobedience, etc.

Therefore, if judges are persuaded, as definition for civil disobedience sometimes are, either not to punish a disobedient or to punish her differently from other people who breach the same laws, it must be on the basis of some feature or features of her action which distinguish it from the acts of ordinary offenders.

Typically a person who commits an offence has no wish to communicate with her government or society. This is evinced definition for civil disobedience the fact that usually an offender does not intend to make it known that she has breached the law.

Civil Disobedience Definition for Kids

, time: 2:00Civil disobedience | Definition of Civil disobedience at blogger.com

Civil disobedience is the refusal to conform to a certain law or policy in a form of peaceful or non-violent political protest. However, it is still illegal and considered as a crime and deviant act as it goes against the law (a formal norm) enforced by the government the act by a group of people of refusing to obey laws or pay taxes, as a peaceful way of expressing their disapproval of those laws or taxes and in order to persuade the government to change them: Gandhi and Martin Luther King both led campaigns of civil disobedience to try to persuade the authorities to change their policies Civil disobedience can be defined as deliberate disobedience of the law out of obedience to a higher authority such as religion, morality or an environmentalist ethic. Civil disobedience has existed in various forms for as long as people have lived in organized societies governed by the rule of law

No comments:

Post a Comment